Tracing their roots back tens of thousands of years, longbows are the great-grandfather of archery. Yes, the longbow’s construction has advanced over the millennia, but its basics remain largely unchanged. That is, it’s a piece of wood bent by a string.

By comparison, the compound bow remains in its infancy, celebrating its 54th birthday in 2020. But my oh my, these mechanical marvels have come far the past five decades.

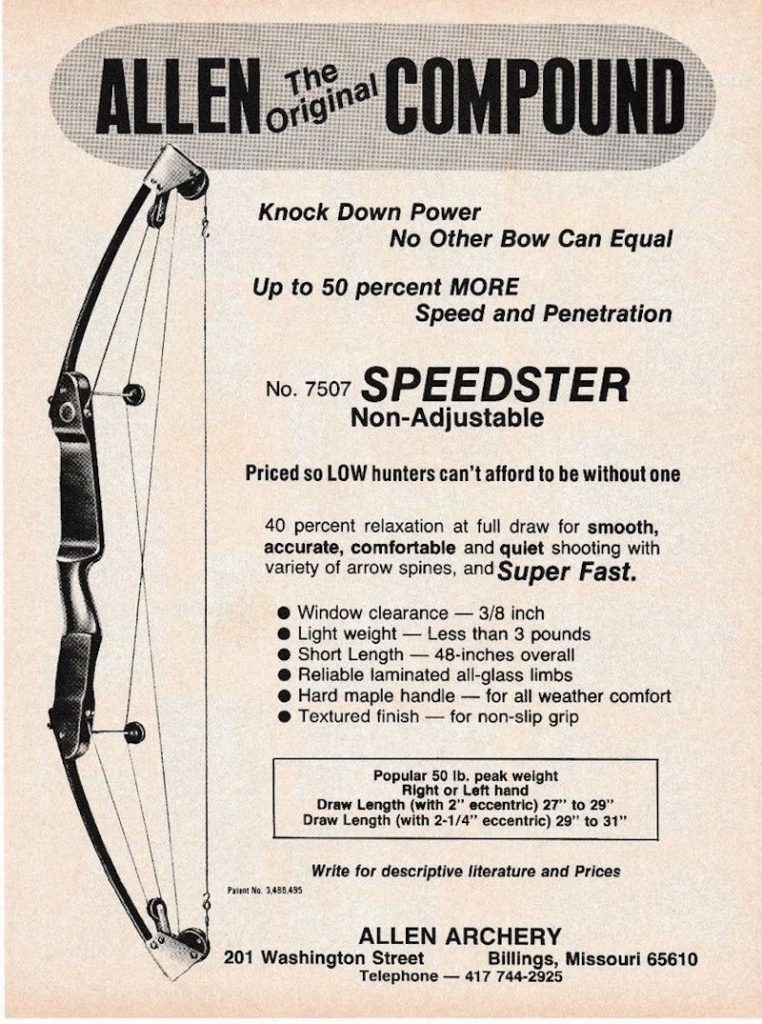

Holless Wilbur Allen, a 2010 inductee to the Archery Hall of Fame and Museum, applied in 1966 for a patent for the first compound bow. It was granted in 1969. The compound quickly evolved into today’s market, with bows made of carbon and aluminum, with huge cams that deliver 90% let-off and arrow speeds over 340 feet per second.

According to the Archery Hall of Fame, Allen was a bowhunter who was tired of game ducking away from arrows he shot from his traditional bow. Using physics as his guide, Allen built bows equipped with cables and wheels to act as force-multipliers to boost arrow speeds. He eventually crafted an effective design, and introduced the Allen Compound Bow to the market in 1967.

That early four-wheel compound didn’t fare well commercially, but Allen let Tom Jennings play with the design. Jennings released the Model T in 1974. That wildly popular bow had only two wheels, and was lighter and easier to shoot.

Early compound bows were fairly long, usually measuring over 40 inches, and most archers drew the bowstring with their fingers. After mechanical release aids hit the market in the early 1970s, manufacturers started making shorter bows.

Today’s compounds run from 28-inch hunting bows up to 40-inch target compounds. Some companies push that shorter end, however, and produce compounds just 17 inches long.

By 1974, eight companies were making compound bows. Just three years later, several more manufacturers emerged, and together they offered archers over 100 models. The compound bow evolved rapidly to expand Allen’s wish to boost arrow speed, while decreasing the amount of strength required to achieve greater speeds.

Many of the early compound’s limbs featured solid fiberglass or a combination of wood and fiberglass. Today’s limbs might use carbon, fiberglass or composite materials. Those early limbs also stood nearly vertical, while today they’re more parallel. Modern designs generate greater arrow speeds with less vibration.

The early compound’s cams were small, round wheels. They served their function, but grew larger over time and took on oblong shapes to increase let-off and further boost arrow speeds.

Martin Archery’s Dynabo in the late 1970s was the first single-cam bow. Its lone cam mounted to the bottom limb, which was more of a rigid aluminum arm. Two cables connected to the cam, stretching up to the maple-and-glass top limb. That top limb was the bow’s only part that flexed. The single cam eliminated the need to synchronize two cams.

Mathews Archery revolutionized the single-cam bow in the 1990s by using a wheel on the top limb to control the string movement. Those Solocam bows matched the speeds achieved by dual-cam bows, but with less hand shock. Simply put, they shot nicely.

The compound’s cables, which work with the cams as draw-force multipliers, were actually strands of steel cable until the early 1990s. Today’s “cables” are actually twisted strands of synthetic fibers, just like bowstrings. These fiber strands are just as strong as steel cables, but lighter and less expensive.

Other advances include the move from wooden risers to aluminum and carbon risers. Some companies in the 1990s also built risers with magnesium — which easily ignites when machined — but soon found it safer and easier to reduce weight by machining out sections in aluminum risers.

Grips on risers also shrank. The compound’s early wood, plastic or molded-in grips were so massive they filled even large hands. Those big grips also created hand torque all too often. Competitive archers quickly recognized this problem, and removed or filed down those grips. Today’s slim grips combat torque.

The connection systems on limbs also improved from those early years, when some limbs pivoted right or left. Today’s bows have pockets that seat limbs soundly and securely.

Speaking of limbs, those initial one-piece models had forks cut into their tips to allow the cams to roll. Split limbs are now the norm. They create a wider limb stance to improve efficiency and reduce vibration.

Tuning compound bows is also getting easier. Within the past two years Elite Archery introduced its Simplified Exact Tuning technology, which lets the archer pivot the entire limb pocket to fix left-to-right tears in paper tuning. Bowtech also launched its Deadlock Cam system, which lets archers turn a screw to drive the cam left or right on its axle to fix tuning issues.

Many bow manufacturers think today’s compound bows are about as efficient and pleasant to shoot as they physically can be. That is, they’re transferring as much energy into the arrow as possible from the bow. Early compound bows wasted lots of energy, but today’s models transfer up to 86% of the bow’s generated energy to the arrow.

Can compounds get any better? Time will tell. The past 54 years have delivered incredible changes in compound bows, but more advances might still await.